For Minnesota Department of Natural Resources Lieutenant Colonel Greg Salo and other participants of the National Association of Conservation Law Enforcement Chiefs (NACLEC) 2016 Leadership Academy, the hope for the three week training was straight forward: learn the principles of adaptive leadership and grow their leadership capacity; network with other conservation law enforcement professionals; and take their new knowledge and contacts back home to address conservation challenges in their home state. “Learning,” “Growing,” and “Networking” are the typical, foundational elements of most leadership programs. What the members of this cohort soon discovered was that this program was not typical. Instead, they found themselves immersed into a months-long experiential learning environment that often seemed chaotic and unsettling.

“We operate under the premise that the barriers to change and progress that officers face out in the world are present in the classroom,” explains NACLEC Executive Director Randy Stark. “We live in a rapidly changing world where trust is a precious commodity and where we face uncertainty brought about by new realties every day. Those two things alone create considerable stress in these administrators’ lives. Often, our natural response to these stressors is to withdraw into the comfort of the familiar. So, in this academy setting we use that discomfort to encourage participants to lean into the discomfort – to hold steady – and seek to understand what is driving the change, the stress, and the barriers to adaptation to these new realties in themselves and the system in which they operate.”

During the students’ second residency at the National Conservation Training Center, their training was put to the test when 42 African participants from the International Conservation Chiefs Academy (ICCA) joined their cohort. The purpose of the joint learning was to enhance transnational relationships in service of combatting international, illegal wildlife trafficking.

“It takes a network to beat a network” Stark said. “It creates a business opportunity for international illegal wildlife traffickers when transnational cooperation is low, and we aim to fix that.”

The African students were from across the continent, and had varied backgrounds, primary languages, and religious beliefs. As the two groups from two different continents eyed each other, those questions of trust and feelings of uncertainty washed over the group.

“But as soon as we began interacting with each other, we found the common denominator with every individual in the group,” said Salo. “While we may have looked different and sounded different, our individual and collective passion for protecting wildlife and wild places bonded us together. We discovered we were more similar than different.”

Salo goes on to say, “Once those relationships were established, our counterparts began sharing the challenges of doing conservation law enforcement work in Africa.”

The stories were shocking.

The U.S. officers heard stories of human/wildlife conflict that involve elephants and lions. They heard the African officers tell of poachers with ties to organized crime networks and terrorists groups. These poachers are well armed and do not hesitate to engage in gunfire. In fact during the 10 year period from 2006-2016, it is estimated that 1,000 African conservation rangers were killed in the line of duty. This number is staggering given there are only 22,000 rangers and volunteers doing this work in Africa. The Africans told of governments that were only decades old and that still experience the negative effects of European colonization. They told of natural resources extraction that takes place with little concern for the environment. In moments of contemplation they wondered whether the elephants and rhinos and gorillas could be saved.

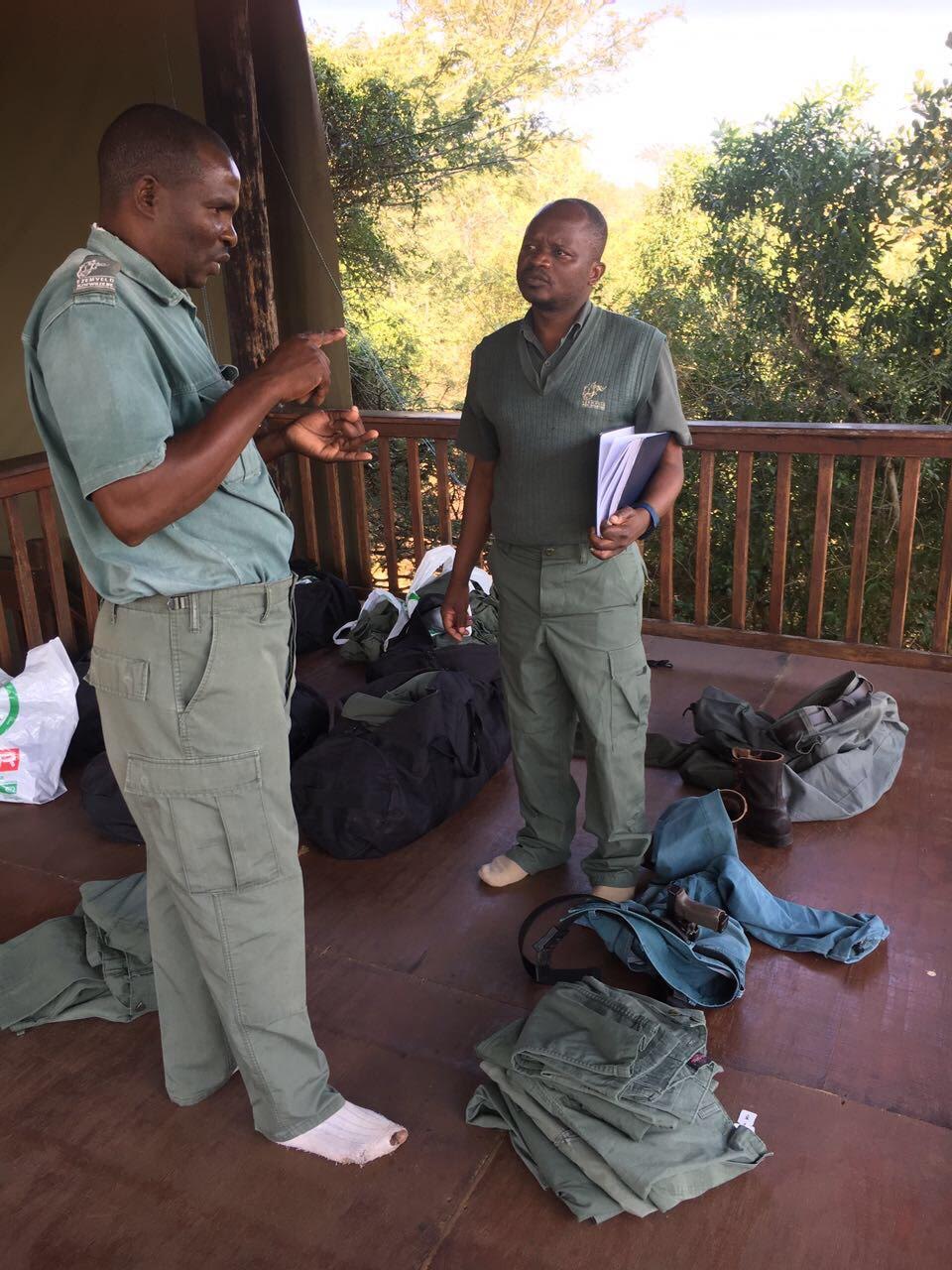

The U.S. officers were stirred to action. While they were concerned about the elephants and rhinos, their greater concern was for their newfound African brothers and sisters. They heard of needs for basic necessities like uniforms, binoculars and spotting scopes. Few of the Africans had protective, ballistic vests. Those sentiments were echoed in a New York Times article from 2016. That article quoted a World Wildlife Fund study that reported of the 570 rangers surveyed in 12 African countries, “59 percent did not have basic supplies like boots, tents and GPS devices.”

Salo and his cohort set out to address this problem.

“Most of our state agencies have a process in which we surplus used equipment,” Salo said in a recent interview. “Much of this surplus equipment is completely serviceable. Often uniforms are simply faded from use and items such as cameras have been replaced with newer models. We thought that instead of selling this equipment for pennies on the dollar, we could donate them to conservation efforts in Africa. It sounded so simple.

“We took a stereotypical game warden approach: we saw a problem, we formulated a solution, and then we applied that action to the problem,” Salo continued. “The Africans needed equipment. We had surplus equipment we could donate. All we had to do was collect the gear and ship it to our new friends. It turned out that it wasn’t that simple.”

Randy Stark put the challenge faced by the officers into the terms of adaptive leadership. “We often rush to apply a technical solution to an adaptive challenge. In this case, the need was clear – many of the Africans lacked basic equipment. Greg and his cohort applied a technical fix, collecting equipment for donation. The aspect they didn’t fully understand were the underlying issues that created this lack of equipment. In adaptive work we always have to assess and identify what structures and mental models are creating these problems. Once we identify those, we can then began to make progress.”

Salo credits retired California Fish and Wildlife Colonel Nancy Foley, a NACLEC peer coach, with helping guide the group through the layers of bureaucracy they encountered and expanding their field of vision of who they should be talking with to move the project forward. One of those was Naimah Aziz.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), Office of Law Enforcement (OLE) is a co-sponsor of this academy. Salo credits OLE’s Supervisory Wildlife Inspector (SWI) Naimah Aziz with guiding the shipping efforts. “Through participation in the ICCA, I have the honor of working with others in the global wildlife conservation community," said SWI Aziz. “Getting the equipment to the designated ICCA graduates was not a simple task: it took over a year, and required perseverance, resolve and teamwork.” With the assistance OLE’s International Operations Unit, and the USFWS senior special agent attachés stationed in Africa, the equipment was shipped and delivered to the African rangers. “To date, this is one of the most rewarding projects I have participated in. It spans all links of the conservation chain including U.S. state officers, wildlife inspectors, special agents, and end-use African rangers.” The Wildlife Tomorrow Fund also played a pivotal role. They utilized their contacts to aid with shipping and their volunteers carried extra suitcases filled with uniforms on one of their trips.

“This ability will work across factional boundaries is a key element of adaptive work,” said Stark. “It requires that a person in a position of authority convene a group of stakeholders and create a space where collaboration around a collective purpose can take place. When we partner with others, we sometimes face differing sets of values and loyalties. These conflicting values and loyalties requires us to consider whether the challenge facing us is worth risking of disappointing our own ‘tribe.’ That’s why true leadership is risky business.”

For Salo and others, the beauty of this leadership program is its approach. “In the classroom we heard the difference between technical problems and adaptive challenges,” he said. “We discussed ‘creating holding environments’ and ‘partnering with authority’ and ‘working across factions.’ The difference in this program is that we took those abstract, classroom terms and tested them on a real problem outside the classroom. And the work we are doing is having a conservation impact around the globe.”

Photos courtesy of Wildlife Tomorrow Fund.